The Slow Match Report: Udinese 0 Bologna 3

Ferguson’s side win by a second-half Alpine avalanche at Miller’s bellissimo new home, but our man in Italy is stood up like a teenager by both Scots

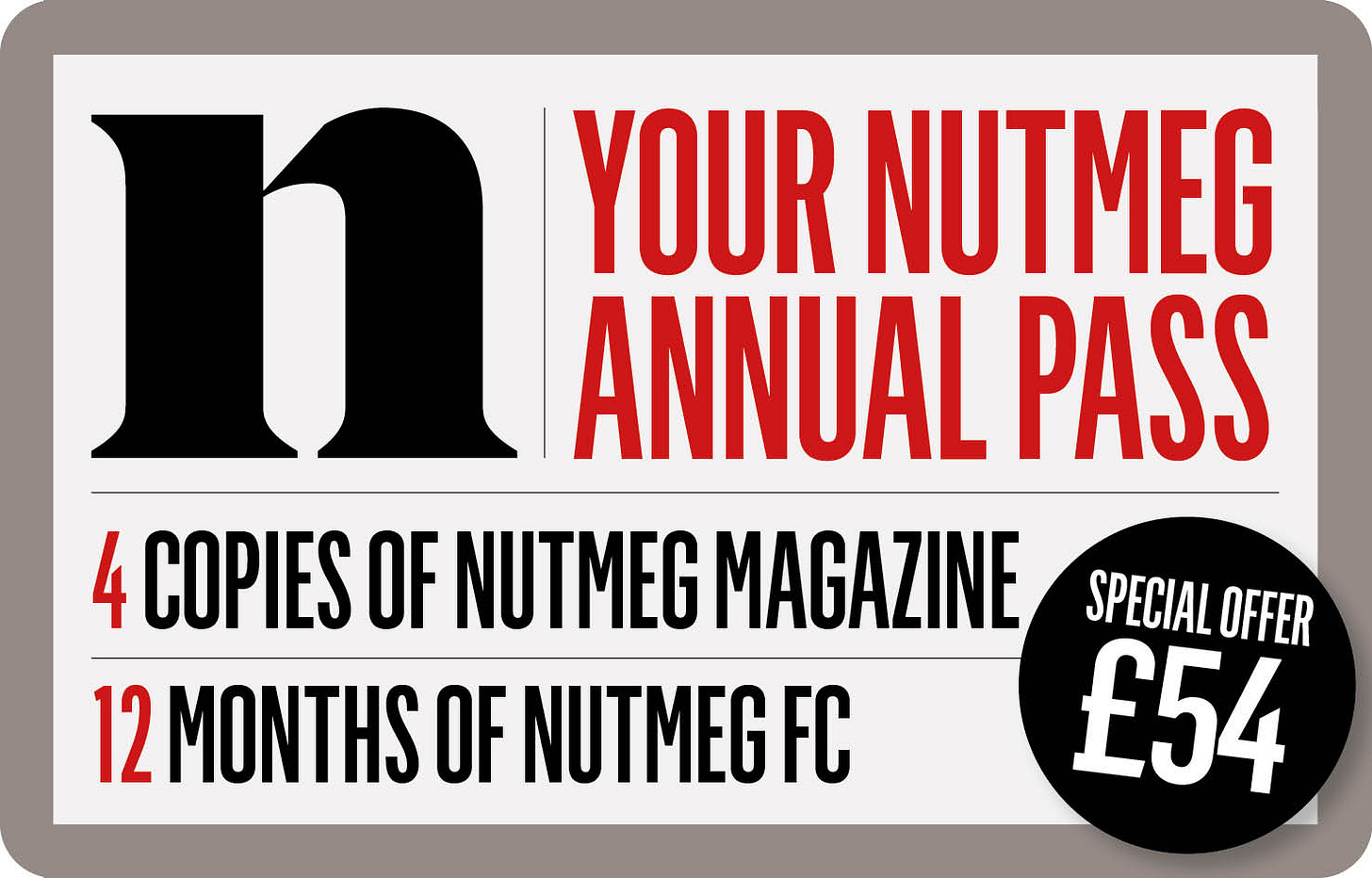

This Slow Match Report is free, but most of our content is paid, such as monthly data breakdowns from Nick Harris, Adam Clery’s tactical analysis and Stephen McGowan’s investigations. Sign up for your Nutmeg Season Ticket to get 12 months full digital access PLUS a year’s subscription to the beautiful, 200-page print quarterly delivered straight to your door.

The big man in the tiny Fiat tooted a symphony on his horn as if he had news to spread. At speed he jolted across the scrubland car park next to the stadium. When he encountered particularly bumpy terrain, his head struck the vehicle’s ceiling. Halted, the man tipped himself uneasily out — it brought to mind a fly attempting to escape from a cobweb — and lifted a black and white scarf skywards. “Udinese alè, alè” he sang several times over, “Udinese alè!” From cities beneath the snowy Alps to dusty sunshine towns, matchday makes happy clowns of us all.

All across the car park, Italians were eating and drinking. Some had brought folding buffet tables which were now spattered with cold meats, bread rolls and cheeses. Others, especially those who had travelled the 100 miles from Bologna, turned their car boots into deli counters and plucked bottled beers from cool boxes. Many queued at the raised hatches of catering vans, whose porchetta made Saturday smell like Sunday. Kids passed balls around. One man showed the kind of prowess that made this both a leading culinary and footballing nation, easily controlling a hard, unexpected pass without disturbing the bite he was taking from a piadina.

Kick-off neared and foil rustled. Leftovers on the way home is perhaps another sacred ritual, stale bread suddenly delectable after a victory. Supporters walked towards the bulbous steel of the modernised Stadio Friuli, itself resembling foil scrunched around a giant focaccia. On merchandise stalls, Udinese shirts hung from rails jerked in the breeze as if trying to follow them. A father and son stopped at one such stand before finally the boy’s grandad tottered near, waving his wallet in the air. I imagined the lad still wearing the scarf his nonno bought him half a century from now.

From high in the main stand could be seen the Carnic Alps, their crooked outline resembling rotting teeth. It was impossible to imagine the mountains’ icy silence, and conceivable that the raised melodies of both home and away supporters in the minutes before 3pm were now causing snow to tumble.

Udinese lined up in their zebra stripes, Bologna in the teal of an expensive fridge-freezer. Their resident Scots — Lennon Miller for the home side, Lewis Ferguson for their opponents — were both substitutes. “So you have come from Scotland to see these two and they are not playing — aagghh!” said the man next to me. Quite. Still, it was something to see their worlds and to know that down there in the dug-out trenches were two men from Lanarkshire.

They watched as French midfielder Arthur Atta repeatedly twizzled his way through several Bologna players, a spinning top. Spiralling free of the defence during one typical raid, he jabbed a pass across goal with the outside of his boot so that it curved as if italicised. Rossoblù goalkeeper Federico Ravaglia was equal, hand-chopping the ball to safety.

Atta’s devilry came to nought; too often his teammates seemed to go weak at the knees in the presence of Bologna defenders, collapsing as if famished. It was like watching blue tits surrendering meekly to robins at the bird feeder. Instead, the away side forced their way forward, rattled into action by Tommaso Pobega, a midfield sculptor with a robust core. The Udinese rearguard looked panicked. Terrified of handling the ball, Kingsley Ehizibue chased around and attempted to stop crosses with his hands joined behind his back, resembling a background chimneysweep dancer in Mary Poppins.

Ehizibue’s concerns, it transpired, were justified. On 35 minutes, Pobega tupped a shot towards goal from next to the penalty area. It seemed to strike the defender’s back and flit from play for a corner kick. Everything stopped. The match could no longer be heard in the Alps. On a screen somewhere, a VAR official was trying to find a penalty as the rest of us might some misplaced spectacles. The wait grew and with it frustration in the crowd, tangible in a thousand hand gestures. It felt a familiar experience. Exasperation at VAR is an international language, a new Esperanto. Finally, a penalty was declared. Hitherto silent men in various browns and beiges leapt to their feet in anger, Jack-in-the-boxes with fresh batteries.

Riccardo Orsolini — a squat tormenting winger, who seems to say, “Now you see it, now you don’t” with the ball — shuffled forward to take it. Diving to his right, Maduka Okoye saved the kick and cradled the rebound like a blessed newborn. The stadium erupted. A verdict had been overturned, moral corruption vanquished. Half-time’s 0-0 felt like a lead.

Something happened to Udinese in the second half, who quite peculiarly failed to ride the wave of righteous indignation. It was as if at half-time their manager, Kosta Runjaić, had sung a bedtime lullaby rather than giving a rousing speech. They were limp and seemed to now witness the game rather than partake in it, as if looking out of the window during a train journey. Bologna’s opening goal was inevitable. Orsolini scampered to the right-hand side of the box, twisting two defenders into wooziness on the way. Next, he nudged the ball to Pobega who absorbed its force and then thwacked it low into the corner of the net. Three thousands tourists from Bologna pogoed.

While that opening goal was earned, the follow-up was a bounteous gift. Twenty yards from his own goal, Ehizibue shoved the ball back to Okoye. Okoye should have hoofed it towards the Alps. Instead, he botched a pass straight to Pobega who clanged it home. Okoye looked forlorn, alone and baffled, a corned beef man in a small plates world.

In their allotted slots, both managers made a stream of substitutions. Each time players were summoned from their warm-ups and the fourth official’s board awoken from standby, my heart skipped a beat. Surely there would be a moment or two for Miller, some fleeting Ferguson. Once more I was 15 years old and waiting outside the Odeon for a girl who was never to show up. “A disaster for you,” said my neighbour, “a disaster.”

Udinese were now decomposing before our eyes, going from rigid to rancid. Bologna missed several chances as if they didn’t want to hurt their hosts’ feelings too much. A mysterious man in a dark suit topped by a black fedora appeared at the end of the players’ tunnel, and I wondered if his job was to ceremonially toll the death knell on performances like this one.

In the 93rd minute, Bologna scored again after more cataclysmic home defending. It was harsh on Okoye, who beyond being the temporary hero in the first-half had repelled much of the shelling his goal took. When he couldn’t save convincingly, he had a likeable unconventional style, at one point flapping for a cross as if wafting a tea towel at a beeping smoke alarm.

Beneath a sky now the black of a switched off television screen, the terminating whistle sounded. Bologna’s players, among them Ferguson, danced a course to the away curva and inhaled their fans’ adulation. I thought about the big man, trying to get back into his car.