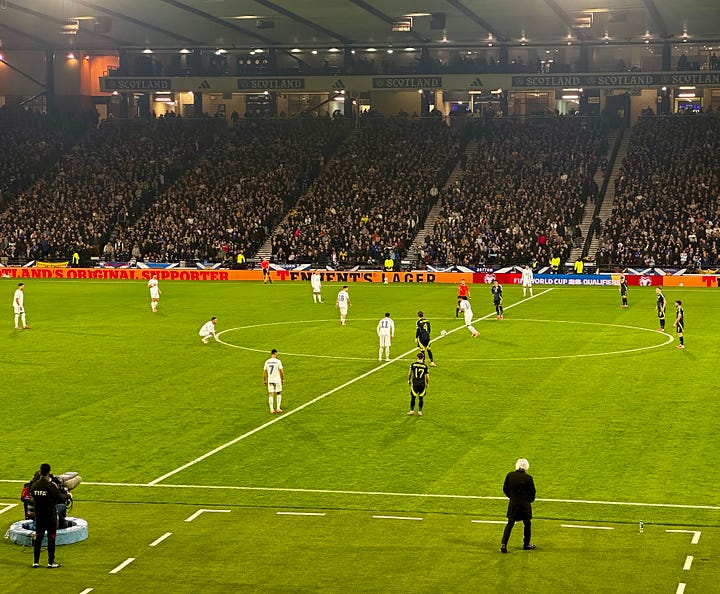

The Slow Match Report: Scotland 3 Greece 1

Not since the rise of Sparta have Greeks suffered such traumatic defeat. It was an injustice, it was moonlight robbery — it was sheer, unadulterated Hampden joy!

This Slow Match Report is free, but most of our content is paid, such as monthly data breakdowns from Nick Harris, Adam Clery’s tactical analysis and Stephen McGowan’s investigations. Sign up for your Nutmeg Season Ticket to get 12 months full digital access PLUS a year’s subscription to the beautiful, 200-page print quarterly delivered straight to your door.

With a colossal ginger moon at their backs, they marched towards Hampden Park. There striding in the cavalcade were the kilted old, the swaggering lads all canned-up and the kitted-out kids. “How many times have you seen Scotland play?” asked a boy of his dad. “Too many,” came the reply.

Standing still meant encountering more moving snippets. “No chance,” said another father as his daughter looked adoringly at a glowing catering wagon, “you’ll gie yer stomach no end o’ grief.” Then came an old man asking of someone unseen, “But ye will be taking your kilt, won’t ye’?” (Away game? Wedding? Halloween party?). Next, a middle-aged woman offered, “That’s me stood in horse manure again. I said I would, and I have.” Perhaps it was a lucky ritual. Round by the away end, a girl of 10 or 11 hauled her dad towards the turnstiles with the power of a shire horse, and merry twenty-somethings caped in Greece flags began to sing. Football’s universality glistened.

The spontaneous pageantry gave way to the enforced. Match officials posed uneasily beneath a burgundy MDF frame. It was perhaps intended to look like a theatre’s proscenium arch but resembled more a stall front at a pharmaceuticals convention. Following the national anthems, brief bursts of UEFA and FIFA theme tunes peppered the air, giving the feeling of being stuck on a bus beside a headphone-less teen sifting through TikTok. Then, at last, came the music of the referee’s opening whistle.

Straight away Ben Gannon-Doak — that bobsleigh of a footballer — spurted down the flank but tapped the ball too far ahead of himself to catch. Scotland’s early plotlines were easy to read: get the ball to Gannon-Doak. They tried to unleash him three or four times in the opening five minutes. On no occasion did it work, a bad anecdote repeatedly told by a drunk.

There were two reasons that the scheme to let Gannon-Doak dodgem his way through failed. The first was an efficient defensive stifling. The Greeks surrounded him like doting grannies over a pram. The second was that he was playing on the left wing. Gannon-Doak on the left is a gift unopened and a toy kept in its box. It is a crime thriller missing its final page and bubble wrap un-popped. It is alcohol-free wine and fishing without a hook. This touchline tempest needs to be on the right, playing so close to the white paint that spectators can feel a breeze in their fringes as he wisps by. He needs to be on the correct wing from which to conjure a sudden belter of a cross as if seeing into the future. He does not need to be cutting inside and encountering a platoon of those doting grannies. Free the Dalry One.

The marooning of Gannon-Doak in captivity was just one factor in what was a stodgy first half from Scotland. Theirs was a mumbling type of performance, a shaky, gnarled, unsure tangle. With their clipped, streamline football, Greece threatened to repeat March’s Hampden mauling. Early on, Anastasios Bakasetas squared for Vangelis Pavlidis inside the six-yard box. Mystifyingly, Pavlidis failed to score. It was as if he was distracted by higher philosophical questions — “Why do some people cover their luggage in cellophane?”, perhaps, or “Is Aunt Bessie a real person?” Later, Pavlidis bashed in a slick shot well met by Angus Gunn in the Scotland goal. In his technical area, Steve Clarke span around with the weary, seen-it-all-before frustration of a man trying to download a large PDF on train Wi-Fi. “Jesus, I’m having the same nightmare again,” cried a man behind me.

“Hel-las!” came the chant from the away corner, “Hel-las!” A cheerful but regimented trumpet suddenly began accompanying them. It gave those of us now drowning in a lagoon of boredom the warm feeling of stumbling upon some village’s civic parade while away on holiday. Greece’s manager, Ivan Jovanović, had certainly dressed for such an occasion, his shoes so polished that floodlight bulbs beamed back from them and threatened to blind anyone within close proximity.

Jovanović wears a white mushroom plume of hair pitched somewhere between Andy Warhol and Gail Platt. It awards him the look of a rock ‘n’ roll bassist who refuses to give in to retirement. At several moments during the first half, I imagined him leaning into the fourth official’s ear and telling him about the time he’d shared a bifter with Ronnie Wood.

A confused bat weaved between Clarke and Jovanović and the referee blew for half-time.

As the second half began, a round of “We’ll be coming…” lapped the stadium. More than a war cry or declaration of intent, it felt like the tired summoning of vague hope, such had been the drowsiness of Scotland’s first-half showing. Their team responded in fashion, lethargically gawping as Greece shifted the ball around prettily. When any player did chase, he resembled a man forlornly jogging for a bus he knew he was never going to catch. The visitors continued to play stylishly, their passing an exhibition. In particular, captain Anastasios Bakasetas — celestial in white boots to chime with the Greek strip — quietly prompted, conducted and arranged, a croupier missing only his gloves.

Greece’s goal, after an hour, was an unsurprising marvel. With trigonometric passes they advanced up the field like spiders building webs. Deft knocks and nudges led to the penalty area where Konstantinos Tsimikas poked home with the precision of a conquering matador. Scottish boos ascended, 10,000 old kettles coming to the boil. They sensed another Greek deluge.

What happened in the remaining half hour proved that football is no beacon of justice, no righteous pursuit. Crawling forwards as if limping away from a lost fight, Scotland burgled a corner. Ryan Christie flew a long, outsize effort to the far end of the penalty area where Anthony Ralston lingered. Ralston calmed the ball and helped it into the box. Centre-half Konstantinos Mavropanos nodded the ball downwards, a flopping gift of a header. Christie had, by now, arrived and with great poise cudgelled the ball into the cage. One-each, somehow, and now Hampden danced.

Greece had a waltz or two left in them yet. With more frolicking football they renewed their terrorising of Scotland. The home side, however, found some resistance and gumption, driven by a reawakened John McGinn and the ebullient substitute Billy Gilmour.

Finally, with not much more than 10 minutes remaining, the Greeks were rattled. Goalscorer Tsimikas elbowed Lewis Ferguson. Andy Robertson trotted forward to have a punt at the resulting free-kick, a dad ambling towards an arcade grabber machine in hope rather than expectation. His cross was the antithesis of Greece’s patient, prissy play. It lolloped through the black sky, provoking the briefest of stramashes before taking a bow in front of Ferguson’s left-foot. The Bologna man walloped the ball as if it had called him a name. Goal. Inexplicable, heinous goal, a Greek travesty. Now Hampden bellowed. Rafters creaked, tectonic plates shifted and America moved a little nearer.

Again, Greece befriended the ball, teasing their way up the pitch. During injury time, substitute Konstantinos Karetsas caressed towards goal a twisting shot that deserved to have a poem written about it. Gunn’s save was equal.

Whichever spell had commanded the last half hour of this match had power in it yet. A Scotland free-kick close to halfway was propelled long, looking for the corner flag or possibly Paisley. A kind of madness afflicted the Greek defence now, though, as it will do to anyone robbed several times over. Goalkeeper Konstantinos Tzolakis came to fetch the ball on the byline but instead pawed at it like a cat with a dead mouse. Lyndon Dykes did the rest and suddenly 45,000 people knew what it was like to get away with murder.

That was a great read- thanks Daniel!