The Hope that Thrilled Me

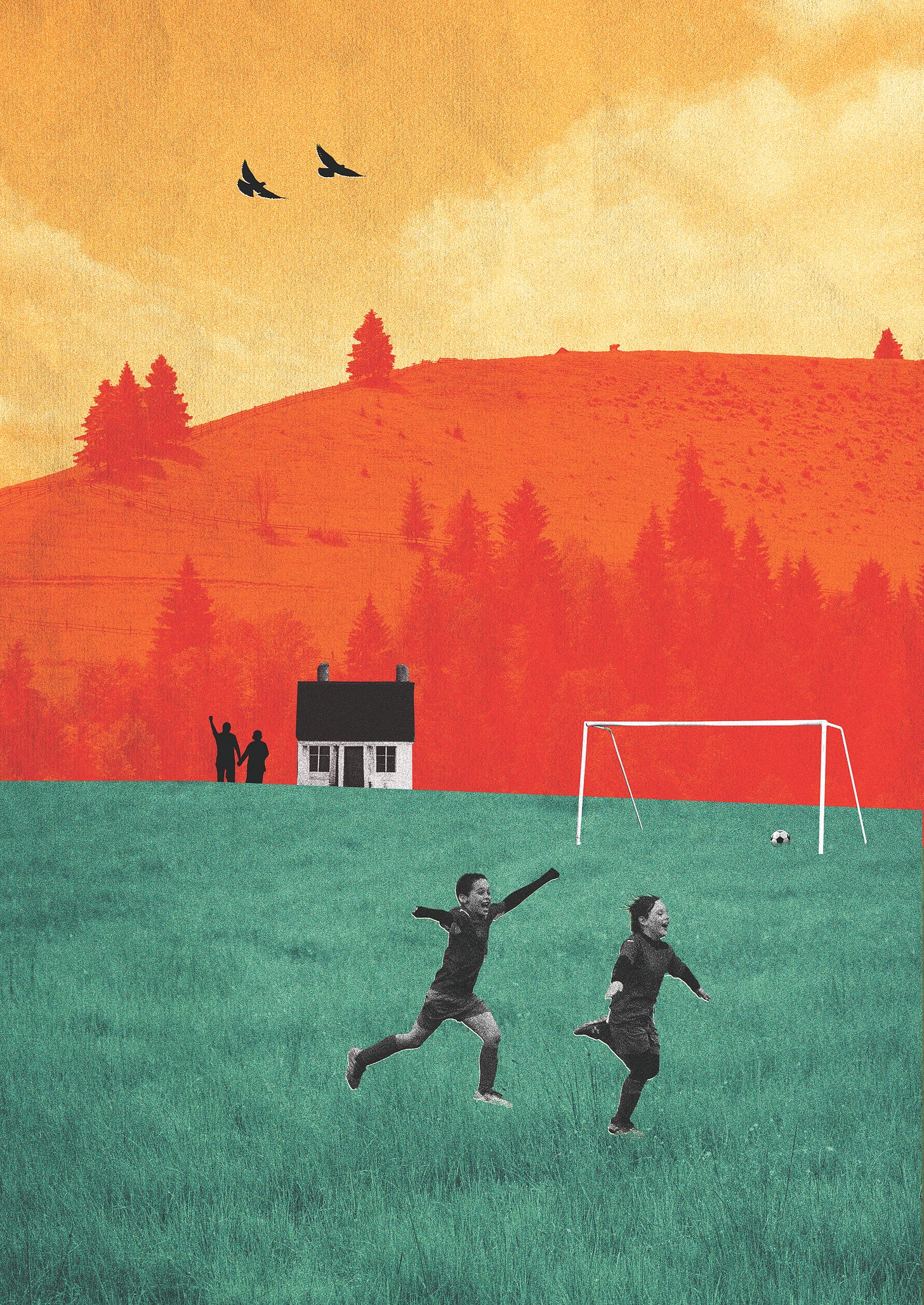

Thinking back to childhood football games on the Moray coast brings time-travel delight. These were our fields of dreams...

This article is a free gift from Issue 35 of Nutmeg’s print magazine, which has been dropping through letterboxes this week — and is packed with insight, analysis, history and fitba culture.

By Gary Sutherland

If I was to draw a map of my childhood in the fishing village of Hopeman on the Moray coast, it would feature the harbour, the beaches and the golf course. Plus the coolest café, which, in the eighties, boasted a banging jukebox, an epic row of arcade machines (Defender! Tron! Popeye! Bubble Bobble!), a pool table, an ice-cream parlour (usually a vanilla double nougat wafer for me) and a chip shop (king-rib supper with pickled onions).

Two other significant landmarks were Maggie’s Green and The Pitch, both fields of dreams where my wee brother and I would pretend to be professional footballers.

Maggie’s Green was a square patch of grass behind our house on Dunbar Street. Beyond this perfect arena for two pre-school kids playing fitba was the home of Maggie and George. Maggie didn’t own the Green, which was separated from her front garden by a dyke. It was just known locally as Maggie’s Green. Maggie and her husband George, two kind pensioners, had a prime view of the action and would lean on their dyke as if they were in the front row of the terracing, watching me and my brother take shots at each other. Well, mostly me firing the shots because Stewart, being my junior, had to go in goals a lot. If a stray ball flew over the dyke, George would throw it back. And when our game was over, Maggie would hand me and my brother a well-deserved biscuit or a sweetie.

The football action raged on all summer apart from the week of The Open

What made Maggie’s Green even more special was that the Sutherland brothers were able to access it through an arch-shaped hole in our hedge, which we imagined was the Hampden tunnel, especially when we were both kitted out in our Scotland strips. Sometimes we were joined by my best friend Steve, who wasn’t really into playing football, so he stood on the sidelines in his jacket, pretending to be Ally MacLeod. The football action raged on all summer apart from the week of The Open when Maggie’s Green became the Old Course at St Andrews and the three of us (Steve joining in this time) took to hitting plastic golf balls around with brightly-coloured plastic clubs. This was fun too, but the football ruled.

When my brother and I were old enough, still kids but now at primary school, Mam and Dad allowed us to take our ball beyond Maggie’s Green and down to The Pitch. Officially called Cameron Park, these are Hopeman’s playing fields. We’re talking Maggie’s Green times a thousand. Not better, just bigger. It stretched all the way from the historic ice house – where fishermen’s catches were once kept fresh before being transported to markets further afield – to the idyllic east beach with its row of colourful beach huts.

At one end of the playing fields: the swings, chute and roundabout. At the other end: the actual football pitch with goalposts. But also, in between, a large expanse of grass that was just ideal for impromptu, small-sided kickabouts with pals, using jumpers for goalposts.

The first of those games I remember vividly was on one hot summer’s day in 1982. It was a big day for Scottish football, beyond even our five-a-side match. Some of us were in shorts, others wore jeans, but all of us were aware that Scotland were about to face the mighty Brazil at the World Cup in Spain. We just had to get our own game out of the way first. In our minds, we were Graeme Souness or Gordon Strachan, or Zico or Socrates. One boy decided he was Eder and even bore a passing resemblance to the Brazilian attacker, though more because of his similarly long rock-star hair and replica Brazil shirt than his dazzling wing play.

We were so involved in our star-studded kickabout that we forgot the time. After the match eventually concluded, Stewart and I were wandering along the street towards our Granny Sutherland’s house when a man called from his front door to say that Scotland had scored and were beating Brazil 1-0. My brother and I sprinted to reach our Granny’s living room.

When we got there, it was quite the scene. Our Dad, in his tartan scarf and clutching a can of Tartan Special, was feeling totally tartan special and roaring at the telly along with the other adults in the room. Stewart and I were handed tumblers of juice, and crisps, then sat down to watch a surprise Scotland masterclass and the greatest-ever World Cup upset.

Except that wasn’t quite how it turned out. We had missed David Narey’s spectacular toe-poked opener but witnessed the remaining four goals in stunned silence as the Brazilians flashed the ball past Scotland goalkeeper Alan Rough from all sorts of sublime angles. The next morning, we were back at The Pitch with our pals for another endless kickabout, every single one of us pretending to be bona fide Brazilians blessed with Samba soccer skills.

Overlooking the playing fields is Hopeman Primary and my first recollection of being involved in a proper 11-a-side game on The Pitch was playing for the school team. I was nowhere near being the most accomplished footballer in a class brimming with talent, but did at least manage to secure a place in the starting XI and found myself stationed on the right wing.

The opposition wasn’t the only thing to contend with. There was the infamous “Hopeman bobble” too. To describe the pitch as bumpy is an understatement. And there were holes like craters on the moon. At least when a bad bounce resulted in you missing the ball completely or shanking it towards the Moray Firth, you could blame the Hopeman bobble. You’d think that local knowledge of this vexing phenomenon would provide the home team with a clear advantage, but that never seemed to be the case. We were all battling a bizarre surface. There was also the marked dip in the middle of the pitch which ensured that whichever way you were shooting, you always felt like you were playing uphill. But it was magic all the same.

The two things I remember most from that well-earned victory over a school from Elgin were the sweet taste of the half-time oranges, and my somersault celebration – in reality, a tame forward roll – after a Hopeman goal I had played no real part in. This earned me a loud ticking off from our headmaster for needlessly showing off and disrespecting the opposition.

The same headmaster disqualified me after I won the sack race on sports day. In my giddy excitement at establishing an unassailable lead, I seemingly ceased jumping and ran the closing yards before stumbling over the finish line. It was enough to see me eliminated in front of my parents. I concede that the headmaster was right to berate me for my over-the-top celebrations during a school football match. But, to this day, I feel aggrieved at him robbing me of my only sporting triumph, other than my victory in the Hopeman café pool competition, which I celebrated with a king-rib supper and a double nougat wafer.

Once school was out for summer, the highlight of the long holidays was always Hopeman Gala Week. You had the raft race in the harbour, the fancy-dress parade, and the five-a-side football competition on The Pitch which attracted entries from far and wide. No matter which team I was involved in, I never came close to winning, but even after being knocked out, I loved watching the closing stages and the final itself. It was fun, frantic and sometimes painful too. Like, for instance, when my class-mate Kev, best footballer in the village with the fiercest shot (think Hot Shot Hamish… he even had the same muscular build and mullet), unleashed a fireball of a penalty kick that somehow was saved by the poor goalkeeper, who instead of celebrating his miraculous feat ended up nursing a broken arm.

Talking of injuries… oh brother. Stewart turned out to be a far superior footballer to me. Whereas my playing career effectively ended with the school team in P7, my younger sibling joined Elgin Boys’ Club and went on to play for Hopeman FC in the local welfare league. Stewart was a classy central midfielder: great first touch, pinpoint passing, ability to shoot from distance and aggressive in the tackle. But, boy, was he injury-prone.

Luckily he ended up with a staved finger rather than a severed one

In addition to splitting his head as a child after crashing his Raleigh Tuff Burner into a bollard whilst eating a salad-cream sandwich, he has broken a knee, a toe, more than one rib, and swallowed his tongue, all while playing football. He once almost hospitalised himself before a match had even kicked off. Helping to put up the nets at Hopeman, Stewart leapt up and caught the ring he was wearing on a hook behind the crossbar. Luckily the ring was cheap and flimsy and broke, and he ended up with a staved finger rather than a severed one.

Then there was the time my dad and I were walking down the steps to The Pitch to watch Stewart in action for Hopeman. We heard the whistle go for kick-off just as we approached but, within seconds, saw both teams and the referee surrounding an injured player on the ground who didn’t appear to be getting up any time soon. “That doesn’t look good,” I winced. “No,” sighed Dad. “It’s Stewart.” Eventually we watched him being carried off.

The most anticipated game in Hopeman was always the home derby against Burghead, the neighbouring fishing village two miles down the coast. These were fierce affairs, not for the faint-hearted, with the rival fans trading insults on the touchline and ramping up the hostile atmosphere. I can still hear some of those clattering tackles on the field. In fact, it’s a wonder that my talented but luckless brother ever survived any of those brutal encounters.

One Hopeman-Burghead clash turned particularly nasty. It wasn’t the players’ fault; the fans were to blame for the match being abandoned. There had been the usual foul-mouthed goading associated with the derby. “You can stick your f***ing Clavie up your arse,” was a favourite Hopeman chant, referencing the Burning of the Clavie, an ancient fire festival carried out annually by the people of Burghead to celebrate the Pictish New Year.

But the flashpoint on this occasion, the single provocative act that lit the blue touch paper, was the Burghead fans producing a makeshift model of the Black Sheddy and proceeding to set it on fire in front of the outraged home support. The Black Sheddy is a shed next to Hopeman harbour where the wise old men of Hopeman have congregated down the years to debate important matters of the day. It is basically Hopeman’s parliament and my Granda Sutherland had a seat in the Black Sheddy. Now the Burghead supporters were torching a crude version of it and the Hopeman fans were livid. No wonder there was a riot.

The people of Burghead are known as Brochers, and they call Hopeman folk Cavers because of the caves near the village. So when one Brocher astonishingly switched allegiances and started not only playing for Hopeman but also skippering the team, the enraged Brochers dealt with the ultimate act of betrayal by christening him Captain Caveman.

But back to my own short – and far from illustrious – playing career. While my final match on the actual pitch was with my school team in P7, my last involvement in an impromptu mass kickabout with jumpers for goalposts took place one summer in the nineties… at around three in the morning. A crowd of us had hit the town in Elgin to celebrate my brother’s 21st birthday. A pub crawl and a trip to Joanna’s nightclub was followed by doner kebabs then taxis back to Hopeman. During the return trip, some drunken hero floated the idea of a game of fitba at The Pitch. Soon we were all down there with a ball in the dark, having to make do with moonlight due to a lack of floodlights.

Teams were picked and the match kicked off. There was no pattern to the play, but I do remember at one point receiving the ball and dribbling past a couple of opponents before shooting past the goalkeeper and into the corner of the, well, just inside the jumper. I duly celebrated my best-ever goal on the Hopeman Pitch with a forward roll and no headmaster to reprimand me. I don’t remember anything else and even wonder if my recollection of my dazzling solo effort is entirely accurate. In the hours leading up to our nocturnal kickabout, I had sunk several pints and a couple of gin and tonics. But I’ll stick to my version of events.

Our moonlit match drew a sole spectator in the form of a villager who lived in one of the houses facing The Pitch. Instead of being annoyed at the racket and telling us to quit it, he settled in and watched the game from his front window. He later proclaimed it to be the best game of football he had ever witnessed.

That was decades ago, and I haven’t lived in Hopeman since then. But I still pop back with my wife and kids to see family and enjoy a Hopeman holiday. And I always ensure that I take my son out for a kickabout. Maggie’s Green is long gone – a house stands there now – but happily The Pitch still exists and hasn’t changed much, apart from the additions of a small skatepark and a pavilion next to the actual pitch.

My son and I take shots at each other (I don’t force him to remain in goals as I once did with my poor brother). Or, better still, he plays with his Hopeman cousins. Sometimes the dads join in, with Stewart demonstrating that he has lost none of his skills.

I watch my boy kick a ball on this field of dreams, covering the same patch of grass I did one summer’s day in 1982 when Scotland faced Brazil. Transported back to those halcyon days yet also wide awake in the present, two kickabouts co-existing magically in a form of football time travel. Smiling at the memories, but also thrilled to be here with the next generation who are just as in love with the simple act of kicking a ball.

Gary Sutherland is a musician, author, journalist and lecturer. He releases music as Vaux Comet, likes to ride his bike, is a big fan of Wout van Aert and once danced with Prince. Gary is a Hopeman man, who lives in Glasgow.