Rohl-ball: Never mind the width, feel the quality

Tortured puns aside, Rangers' coordinated centralised attacking which unravelled Hearts could make Danny the Champion of the World (or Scotland, anyway)

Hello. Quick question. Am I too late to use “Rohl with it”? Has that already been done to death? Were they doing this within a week of him joining Sheffield Wednesday? It’s had its moment, hasn’t it? That’s a shame for me.

Anyway, heartbreak parked to one side over losing this open goal of a pun intro (Rock and Rohl? Rohl Reversal? Rohl Model? I’ll figure something out later), it’s been quite the season for Rangers. I’ll skip the “Previously On…” for you and say, simply, that Russell Martin was the worst appointment I’ve seen since I was mistakenly called for a colonoscopy while waiting at the GPs.

Before you get into the whys and hows and whathaveyou, the most important thing to observe about Rohl-ball (all balls ‘rohl’, technically) is the foundation of solidity. Rangers had recorded a solitary clean sheet in the nine games prior to his appointment, but now have 10 in the 19 games he’s managed. That’s also one win, and then 14 of them, respectively, across the same periods which is, scientifically, Not Shit.

But getting your clean sheet percentage up from 11% to 53% — which are, sure, really gratuitous stats that nobody would ever actually use but I did work them out for my own curiosity and didn’t want that small amount of work to go to waste so there you are — is not what’s impressive here. Cobbling together a title charge, and talk of a ‘double’, after starting the season under the stewardship of statistically the worst manager in the club’s history, is.

If Rohl pulls that off, it’ll be a success built on the foundations of the lesser-spotted 4-2-2-2. Not entirely, mind you: he messed around with a back five in his first two games at the club, much like he’d done at Sheffield Wednesday prior, but this system was always what he was building towards. That it blew away Hearts, their most pressing challenge, felt fitting in both a quiet and extremely loud way.

A short history lesson for you. Danny Rohl learned an early chunk of his trade in the Red Bull system, and another more practical wedge working under Ralph Hasenhüttl at Southampton. The thing these environments have in common is a keen enthusiasm for centralised attacking. Regardless of the formation, Rohl comes from several different schools of thought that believe football is to be played, where at all possible, through the middle of the pitch.

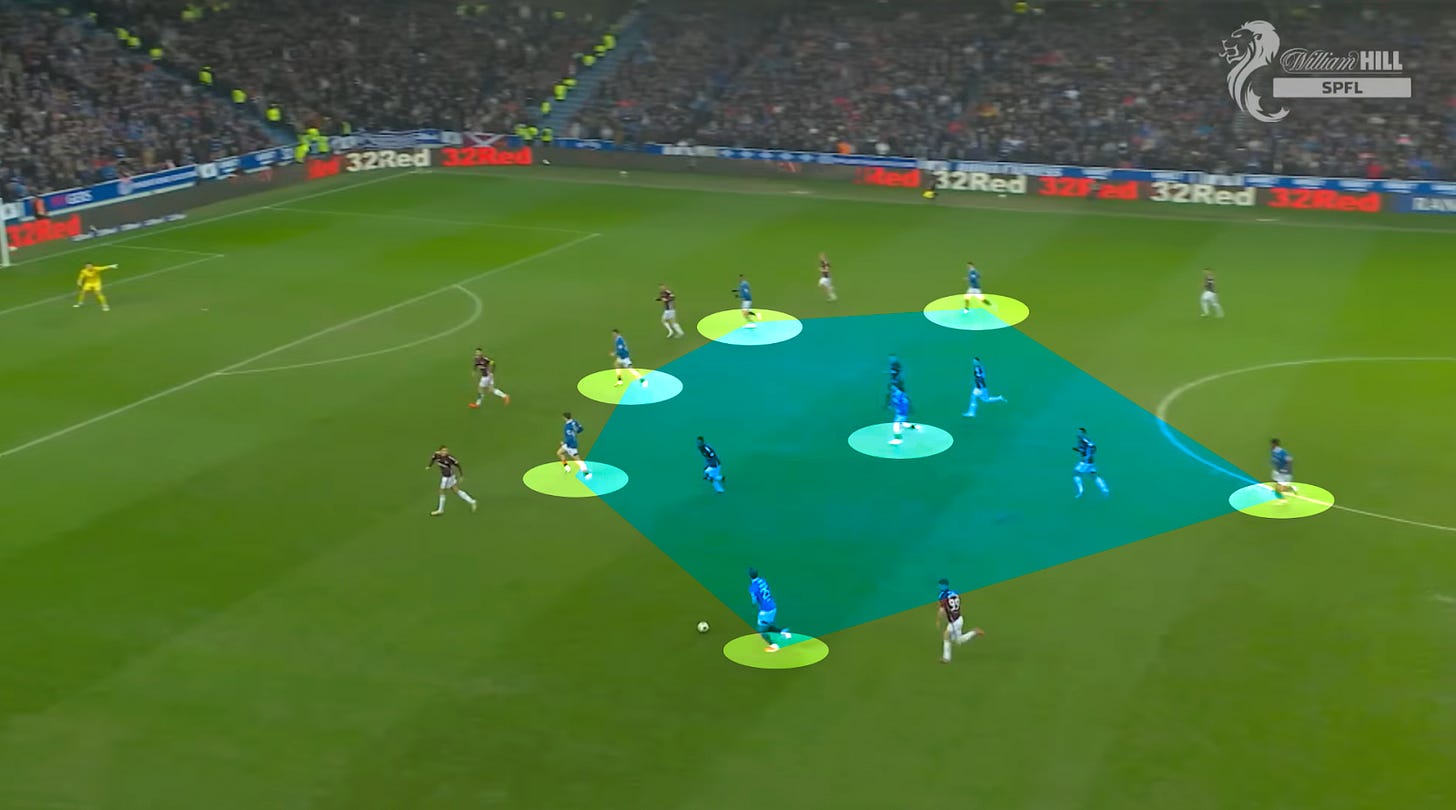

Like, what do you notice here? Rangers flooding forward with the ball, committing seven players to the attack, and you could throw an (admittedly enormous) tea towel over the lot of them. No real interest in holding width, nobody looking to get tight to the touchline, not one little thought about “stretching the defence” in their heads; just coordinated centralised attacking.

There’s not one player in this attack who doesn’t have a teammate within about 10 yards. And the nearer to the centre of the pitch they are, the closer proximity to a colleague they are as well. You’re not seeing a 4-2-2-2 in that picture but you are seeing the benefit of one.

The rest of this article is for paid subscribers. Been waiting for right moment to support the best football writing in Scotland?

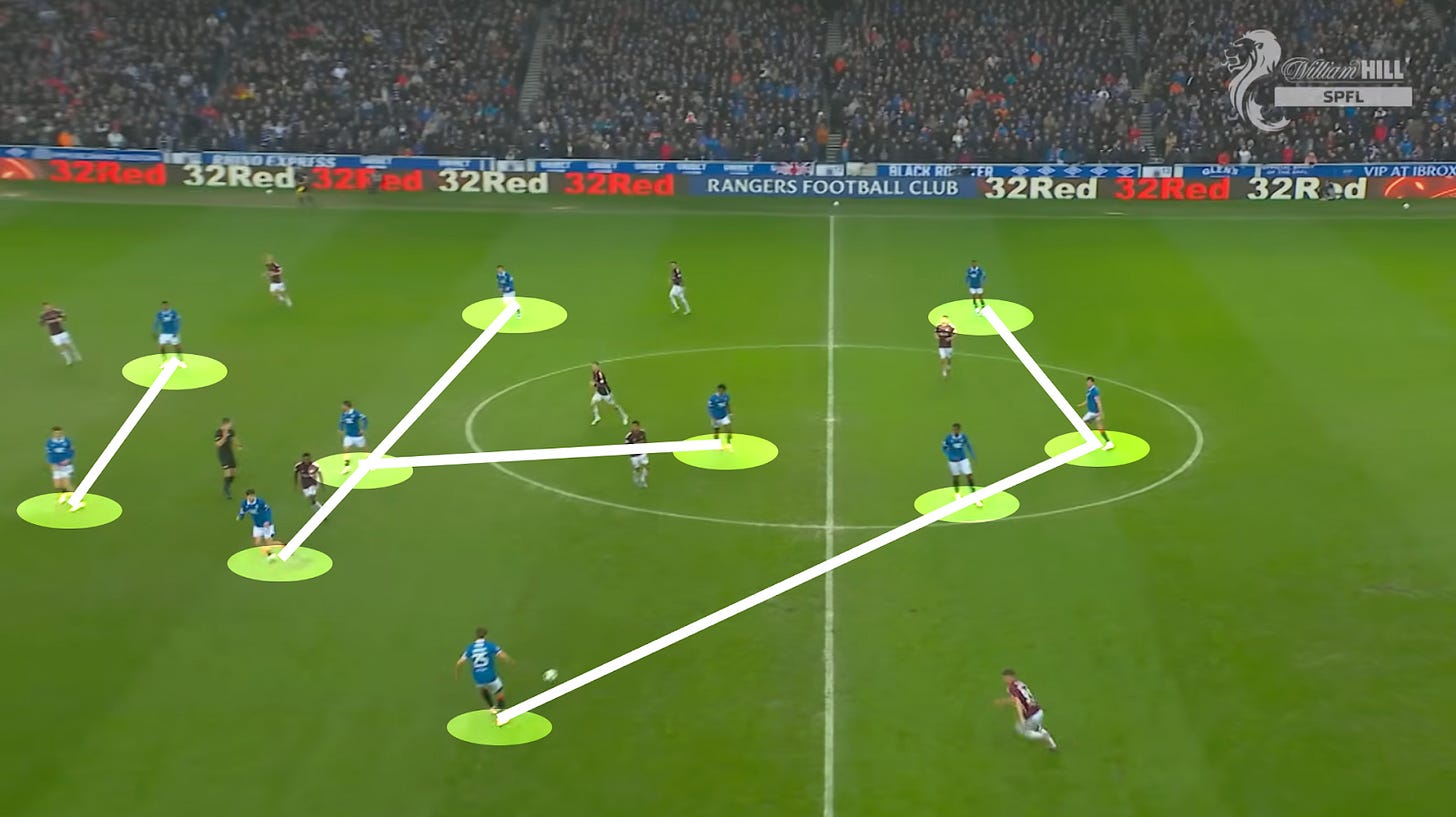

Rohl has said it himself in interviews, but the idea is to have central pairings that both support and complement one another straight through the centre of the pitch. Two centre-backs, two 6s, two number 10s and two centre-forwards. They can sit together and be solid, so it’s great out of possession, but they can also take up different vertical positions, safe in the knowledge that the space they leave is covered.

This is a few seconds prior to the image above, with the pairings highlighted so you can see how they move. The forwards and the 10s are occupying their normal positions, the former looking to pin the centre-backs and the latter looking to get into the space that might leave, but the 6s have split, with Tochi Chukwuani dropping nearer to his defence as a passing option and Nico Raskin jumping up to occupy the emerging gap between the lines. Again though, you’ll notice… still nobody out wide.

What width the side has comes in two forms. First off, the full-backs are there, and theoretically they can advance and retreat to give any pairing of two a wide outlet depending on where you’re playing the game. They’ll make it a 2-4-2-2 in certain phases of build-up, a 2-2-4-2 if they’re on the edge of the opposition box — you get the idea.

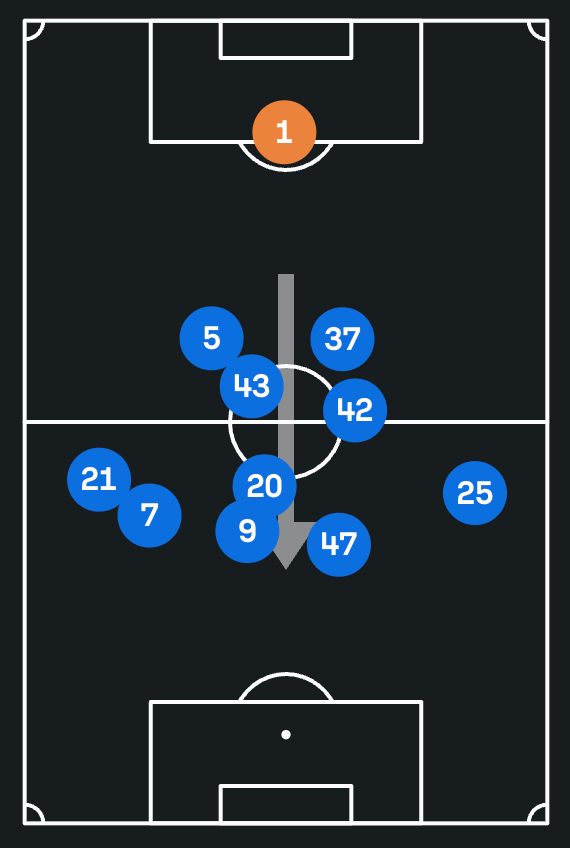

I have no idea if you personally use average position graphs with any regularity but, if not, let me assure you that’s a very weird looking one. Andreas Skov Olsen (who I’ll show you in a second) is the only player not-a-full-back to wind up with an average position not squarely within the width of the 18-yard box. Which brings us around neatly to Width Option B: flexibility. None of the players are encouraged to hold wide positions, but they can occupy them if it presents creative solutions.

Take the third goal. The player on the ball here is Dujon Sterling, the right-back, who is the one providing the width down that side. But the aforementioned Olsen has just gone and stood on the touchline, with an absolute yawning chasm between him and anyone from the midfield who’d ordinarily have been marking him. It’s the second phase from a corner he took, I’ll grant you, but he makes no effort to return to his actual position and, instead, just stays where the space is.

Hearts’ title challenge is, roughly, 98% built on how difficult they are to play against and yet he finds himself with a space the width of Buchanan Street to swing the ball in for the goal. All from just being a little bit flexible with his role.

What’s telling about this brand of football is that it’s not easy to either coach or play. Six players all occupying the central areas is great when it works, but done badly it’s a congested mess that hinders more than it helps. Likewise, the full-back roles require defensive work-rate, technical competence, and attacking verve to a level that exceeds even your common wing-back. You can’t just turn up and get 11 random lads to give it a go.

Rangers were active in the transfer window though. Chukwuani, Tuur Rommens, Ryan Naderi and that man again Olsen all arrived for a not inconsiderable £12million. All four of them started the victory over Hearts, with one at full-back, one at 6, one at 10 and one up front. Rohl urgently installed a spine into the team that was comfortable playing this brand of football, and the results were immediate.

He knows this system, he knows what it can do, and he’s already got a team that knows he’s right. Can Rangers win the title? Well, they’ve got better odds than just a Rohl of the dice, haven’t they? (HAHAHA!)

A big difference without Barron. Playing on the front foot without him and his continual backpass .