Welcome to a new episode of the My Sporting Hero podcast, part of Nutmeg FC. The home of brilliant football stories — made in Scotland.

So far this month, Nutmeg FC subscribers have enjoyed....

The exclusive column from our tactics guy Adam Clery — on Scotland’s friendly double header against Iceland and Liechtenstein.

Daniel Gray’s Slow Match Report from the Shelbourne v Shamrock Rovers League of Ireland clash.

And still to come....

The latest column from Nick Harris — author of the brilliant Sporting Intelligence blog.

The latest three-part investigation from award-winning sportswriter Stephen McGowan.

Only paid subscribers to Nutmeg FC get every piece we produce straight to their inbox.

This time on My Sporting Hero, our guest is Maurice Ross.

Dundonian Maurice played as a full-back, most famously for Rangers under Alex McLeish.

He won two league titles, two Scottish Cups and two League Cups (scoring the opener in the 2005 final) with the Ibrox club. After leaving Glasgow in 2005, Maurice embarked on a globetrotting career that took him as far and wide as England, Turkey, Norway (most notably with Viking FK) and China. He was capped 13 times by Scotland.

Maurice went on to coach and manage different clubs in Norway and the Faroe Islands, was boss at Cowdenbeath and his last coaching role was as assistant manager to his old Gers team-mate Charlie Adam at Fleetwood Town. Maurice takes a particular interest in teaching youth footballers not only soccer skills but also life lessons and self-motivation.

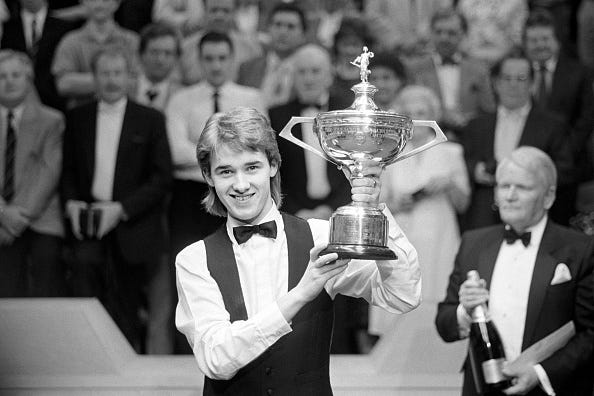

Maurice’s sporting hero is Scotland’s snooker superman Stephen Hendry.

Back in the day, there was only BBC1, BBC2, ITV and Channel 4, and we never had Sky or cable so I seldom got to see big football games or other big sporting events. However, the snooker was covered by the BBC and it meant top sport on the TV for two weeks. Stephen Hendry was living just down the road in Stirling, and I became fascinated with the sport.

Stephen was only 16 or 17 when he broke onto the world scene and went up against guys like Steve Davis and Jimmy White. These guys were stars, and Stephen Hendry was throwing a spanner in the works. I remember interviews in which he said he would practice for six hours a day, and I thought it was unbelievable that he had the discipline to do that.

My granny was also really into snooker, and I remember getting a tiny snooker table. It must have been four feet, the cues were terrible and the balls were gobstopper-size, but I was so proud of it! Sometimes at lunchtime I would sneak home without my mum’s knowledge and play a couple of frames, and I just got totally into it alongside football, of course. I was seven or eight when I got my table, but when I was older, I would play on proper tables at a place called Maryfield in Dundee with my mate and you would realise just how hard the game is.

I never got a hint of any arrogance in Stephen. Maybe other people did, I’m not sure. But to have had the determination and the discipline to spend six hours a day practicing middle-bag pots at a young age, he must have had really strict, strong parenting behind him. He must have had that to possess the backbone to be on television — and there are probably 10 million people watching on that Sunday night at the Crucible. It’s exceptional.

I’ve gone on to love Ronnie O’Sullivan, but I was kind of gutted when he became better than Stephen Hendry. He was part of my growing up, and part of my life with my granny as well. I had a black-and-white TV in my bedroom. It sounds crazy, watching snooker on a black-and-white TV, but if a big match had gone on past my bedtime, I had no choice. I used to try and wangle it so I can stay at my granny’s because she would let me stay up and I could watch it on her colour TV. My granny has passed away now, and she would start shouting at the TV in broad Dundonian as though Stephen could hear us! I have fond memories of watching the matches with her, eating a fritter roll or something from the chippy. Memories like that give me good feelings.

I respect how good you need to be to play snooker, although I see how much planning goes into any sport. A golfer has a myriad of factors to consider when he is preparing to take a shot — wind, moisture, air temperature, grass conditions, etc. — and this all plays into my football coaching techniques; I teach that it’s thought process that affects output. And when you consider snooker, these players are planning four shots ahead, which is outstanding. Yes, there’s discipline and talent, but it’s very much driven by thought process.

When I consider guys who stand on their feet for six hours a day practicing, training their mind to not get bored and still have the discipline to train like that when they’re number one in the world and earning millions of pounds, I admire them. To get to the top is quite something, but to stay there is a totally different ballgame and Stephen was the best in the world for nearly two decades. Then Ronnie O’Sullivan came along. O’Sullivan for me was a mix of Stephen Hendry and Jimmy White, and that’s what makes him so fabulous and so well-liked because you know, as good as Jimmy White was, he never quite won the World Championship. Scotland as a nation has produced many one-off sporting greats and Stephen Hendry was certainly one.

He looked up to Steve Davis and I’m pretty sure Ronnie O’Sullivan looked up to Stephen Hendry. But what fascinated me about Stephen was that he never got perturbed by anything — he always looked like it was all going to plan. Whereas Ronnie’s a bit more erratic and a bit more volatile, which adds to the drama. But with Stephen, it was like he never spoke. It was as though he just went home, slept, woke up and played snooker. I don’t know what it would be like to live with someone who was that dialled into their profession. It’s probably really difficult and most top athletes do have issues with family life because they’re addicted to their sport, which means they cannot give everything to everyone.

Stephen was so determined whereas Jimmy White had, I think, a flaw — he had so much talent, but there must have been something inside him that spooked him. Whereas Stephen just seemed to be like a robot that did not flinch. It was phenomenal. I remember Stephen missed a black into the middle pocket against Mark Williams which should have been easy for him, but it shows you how great he was that you were really surprised that he missed a shot.

There was the natural talent in Stephen, but that consistency came from him practicing every day. It’s the same with all sporting greats — if you listen to Michael Jordan, Tiger Woods or whoever, they all talk about the same stuff: working on your own, not listening to the noise, focus, failing but keeping going. And we then see this final product that we all want to be associated with because it’s success, but nobody’s associated with you when you’re doing the hard yards behind the scenes. Applying that to footballers, it’s about asking yourself what’s going to make you better, what are your thought processes and physical output, how dedicated are you to what you’re putting in your body. All of these things are controllable, and then that muscle memory kicks in when you go in the pitch because you’ve been training since you were a nine-year-old.

It’s the mind that controls it all, and as I mentioned earlier, it’s about having a family behind you who have brought you up a certain way. “Show me the boy at seven, I’ll show you the man”; I’m a big believer in that. My mother taught me to be punctual, to have my boots polished, to not stay out bevvying with my mates, and she also had a chores rota when I was growing up — that all inadvertently instilled discipline in me. And then you play with super-disciplined men like John Brown and Richard Gough, and you realise that you are already disciplined yourself.

There’s more chance of being a Scottish footballer than there is being a world-class snooker player, but it doesn’t matter what level you’re at and it doesn’t matter what your career is, if you don’t have passion and put everything into whatever you do, it’s always going to be average. If you do the best you can, you’ve always got a chance. Now your ability might only take you to an average level in your particular field, but at least you can say to yourself at night, “I’ve done my best.” My granny used to always tell me that you can’t lie to yourself.

I’ve never met Stephen Hendry, in fact, I’ve only ever met one snooker player, Ken Doherty, who was a smashing player as well. I would love to meet Ronnie O’Sullivan because he just fascinates me, but I would truly love to sit and have a cup of coffee with Stephen Hendry.

I like the way the snooker TV commentary is honest and critical. It is therefore true to its working-class roots. Whereas football commentary is dreadful now, it’s full of sycophants who just want to please the broadcaster. It is dull and banal, just superlative after superlative. There is no meaningful analysis of why something happened in a game. So when you hear Stephen Hendry and John Virgo giving an honest appraisal, telling you why a shot was great, I love it.

Anyway, I don’t think snooker players listen to the criticism, because they are so insular — they’ve got to be, because if they are having an off-day, they don’t get paid. In football, I can have an off-day in training or in a game and my teammates can pull me through. I remember hearing something that always stuck with me: snooker is an individual sport, but in other individual sports it’s different — a golfer always gets to have a shot, a tennis player always gets the opportunity to return the ball, but in snooker, your opponent actually gets to stop you plying your trade. You don’t get to play if your opponent is on it. You’re sitting in that chair for six frames and Stephen Hendry’s wiping the floor with you and you cannot get a shot. The only shot you get is the break, which even then is alternate. So it’s a fascinating sport. I love it.