How the Scotland team’s insurable value bodes well for our World Cup hopes

For a decade, this unique data modelling has been largely accurate… so you’d better strap yourself in for a group qualification party

A statistical model based on Sporting Intelligence data that calculates the insurable value of international football squads has been largely successful in predicting outcomes in major tournaments for the past 12 years.

Today, in this first piece of 2026 for Nutmeg, and as a World Cup looms this summer, I’ll be analysing the insurable values of the four nations in Scotland’s group (Group C) at the tournament in the USA, Canada and Mexico.

Scotland qualified for a first World Cup in 28 years in November, on a hugely emotional night (below) after a 4-2 win against Denmark that literally shook the earth.

By quirk of fate, Scotland’s last appearance at a World Cup, in 1998, saw them placed in the same group as Brazil and Morocco (and Norway), and at the 2026 World Cup they will be in a group (again) with Brazil and Morocco, and Haiti.

Scotland will start this summer’s tournament by playing Haiti on June 13 (June 14 UK time) in the Gillette Stadium in Foxborough, Massachusetts. On June 19 they will face Morocco at the same venue, and then on June 24 they will end the group stage by playing Brazil at the Hard Rock Stadium in Miami.

Scotland, infamously, have never progressed beyond the group stage of any major tournament (World Cup or Euros) and back in 1998, they finished bottom of Group A after losing to Brazil and Morocco and drawing with Norway for a total of one point from three games.

This summer’s World Cup will have a different dynamic. For the first time there will be 48 nations involved, and 32 of them will progress to the knockout phase, meaning that after 72 group matches (six games in each of 12 groups), only 16 teams will be eliminated. Which means that eight groups of 12 will see a third-placed team through to the knockouts. A single win might well be enough to get through to the last 32.

Before I get into the details of what I think will happen in Group C this summer, some background information about how the insurable value model came about, and the logic that underpins it.

In Spring 2014, I was contacted by an analyst at the Centre for Economics and Business Research (CEBR) in London, asking if Sporting Intelligence could provide some salary data for England footballers who might play at that summer’s World Cup in Brazil.

I’d just published the fifth edition of the Global Sports Salaries Survey (GSSS), which ESPN The Magazine also published, in a deal where they paid Sporting Intelligence an annual fee for, in effect, first rights to reproduce my GSSS research worldwide each year. We worked together in 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014 and 2015 before I collaborated with other partners from 2016 onwards.

The CEBR wanted access to my data, the data that underpinned the GSSS, and they quickly went from wanting just the England data to data for all 32 competing countries in the 2014 World Cup. Sure, I said, I’ve got most of it already, for something like 70% of the 736 players who will be in Brazil, because they’re in my database. Give me time and I can pull together the rest.

My CEBR contact then revealed to me that his client was actually Lloyd’s of London, the global insurance underwriter. Lloyd’s wanted to try to predict the winner of the 2014 World Cup by the players’ insurable values as a publicity exercise. And the CEBR was building a model to try to do that, but didn’t have access to reliable salary data, the single most important input.

No problem, I said. On the basis that wages are a proxy for talent, and that highly paid young players are the most talented, the model adjusted the data to provide the insurable value of each player.

Long story short, I supplied the data to the CEBR, and they fed it into the model. They then realised they wanted a lot of other metrics they didn’t readily have, such as contract lengths and football inflation, and I gave them that, too.

the prediction proved right, and Lloyd’s got lots of coverage

The upshot: Lloyd’s were able to predict that Germany, then the fourth favourites, would win the 2014 World Cup. And that prediction proved right, and Lloyd’s got lots of coverage afterwards, which was the point.

We did it all over again in 2018, and again Lloyd’s were able to predict that France, then the fourth favourites to win the World Cup, would triumph in Russia. And they did.

Not only did the 2018 Lloyd’s model predict the correct winners, but it came out top in an evaluation of selected predictions for the World Cup. This was collated by Prof Roger Pielke, then the director of the Sports Governance Centre at the University of Colorado, Boulder, USA, on behalf of the Soccernomics agency.

The Lloyd’s model, underpinned by Sporting Intelligence data, beat others from organisations as eminent as Goldman Sachs, Nate Silver’s FiveThirtyEight, investment banking giant UBS and sports metadata firm Gracenote among others, as well as outperforming predictions based on the FIFA rankings, ELO rankings and transfer spending data.

Together we went for a hat-trick in 2022 for the Qatar World Cup, but England and Brazil, the model’s choice of finalists, both fell in the last eight, while the model’s third and fourth favourites, France and Argentina, ended up contesting the final.

By Euro 2024, Sporting Intelligence had moved to this platform, Substack, and while the model failed to predict the winners, a lot of the group predictions were accurate.

In Group A, we said Germany would top the section ahead of Switzerland in second, and that’s what happened. In Group B we predicted a Spain-Italy-Croatia-Albania 1-2-3-4 and it happened. In Group C we went for an England-Denmark 1-2 and it happened.

We got Group D wrong, saying France-Netherlands-Austria-Poland, when in fact it was Austria-France-Netherlands-Poland. Football, eh? Bloody hell.

Group E was also a bust, Belgium not winning as expected while Romania topped a group where all four teams got four points.

By Group F, we were back on track with Portugal-Turkey forecast to be 1-2, which they were.

In the knockouts we thought England would be in the final (they were), but not against Portugal as predicted but Spain. We got six of the last eight correct.

Anyway, onto the 2026 World Cup and Scotland’s fate.

Today’s piece will tell you:

The insurable values of the squads of Brazil, Morocco, Scotland and Haiti.

The most valuable player in each squad, in terms of their insurable value.

The number of players in each squad with insurable values of more than £100million, and of between £50m and £100m.

The predicted ages of the squads that will go to the World Cup this summer, and what that might mean.

Where we would realistically expect each team to finish in the group, based on their insurable values, which effectively reflect the quality of those squads.

How this tallies with world rankings and bookmakers’ odds.

The rest of this piece is for paid subscribers. Been waiting for right moment to support our indie journalism? Then sign up for our Nutmeg season ticket offer now…

Before we get to the key details, some caveats. It’s January and nobody in their right mind would claim they could accurately predict the make-up of the squads for the 2026 World Cup. Injuries, form and a multitude of other factors will change managers’ minds between now and the summer.

This means I’ve picked the most likely 26-man squads for each of the four countries in Group C. This is based largely on the most recent squads that played competitive matches for each country, with tweaks to include players not involved in those games but likely to be in strong contention later this year.

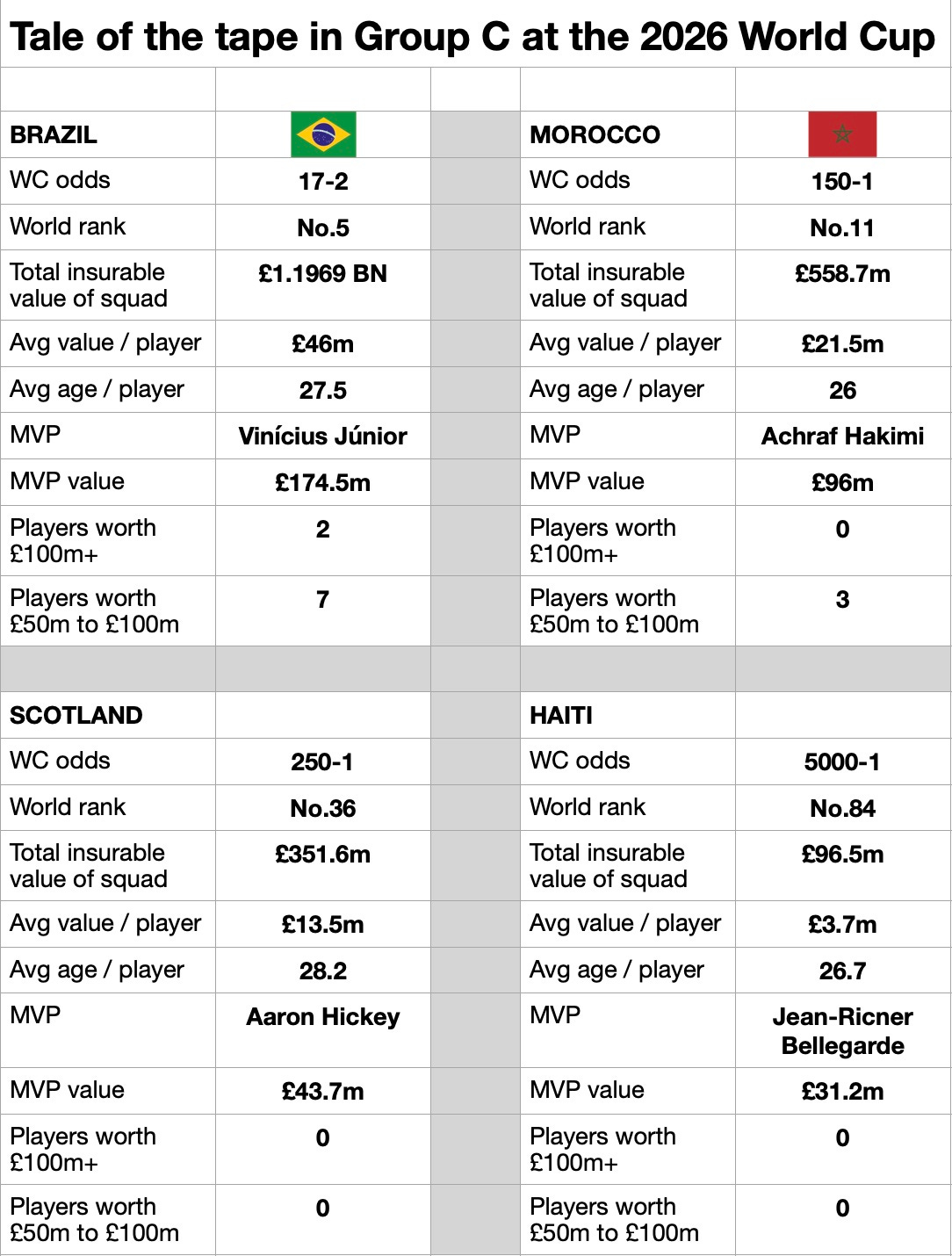

In the graphic below I summarise the world rankings, odds and ages of each of Group C’s participants. By both odds and rankings, one would expect Brazil to top the group, with Morocco second, Scotland third and Haiti fourth.

The insurable values of the squads also predict that outcome, with Brazil’s players collectively worth £1.2billion in insurance terms (a long way short of their £2bn+ valuation at the 2022 World Cup), Morocco’s worth £558.7m, Scotland’s £351.6m and Haiti’s £96.5m.

I’m predicting that Scotland will have the oldest squad, averaging above 28 years per player, followed by Brazil (about 27.5), then Haiti (26.7) and Morocco (26).

Just for comparison, winners Argentina in 2022 had a average age of 27 and a bit, while winners France in 2018 had an average age of 25.6, and winners Germany in 2014 had an average age of 26.

Let’s face it: Haiti aren’t going to be winning the World Cup, so if youth is an asset then Morocco will do well, and Scotland not so well, while Brazil’s squad is not of the calibre of many previous tournaments.

Before we move onto the analysis of individual player values, here’s the graphic in question.

So who has the highest insurable value, and why?

If we start with Brazil, then it’s Vinícius Júnior of Real Madrid, age 25, who is their most valuable player in insurance terms, worth £174.5m. Only one other player in Group C has an insurable value of more than £100m and that’s Rodrygo, 24, also of Real. Brazil have a further seven players worth between £50m and £100m.

To grossly simplify the methodology used to produce these numbers, we try to assess the future career earnings of each player up to a nominal retirement age of 35, and in the case of players already that age or nearing that age, the value of their current (and probably last) professional contracts.

Again, to simplify things, if a young player is already at a big club on a big salary, then they are going to have a much higher insurable value than a much older player, or indeed a player of their age but at a much lesser club.

The seven Brazil players worth between £50m and £100m in insurable values, according to our model, in descending order, are Éder Militão, Bruno Guimarães, João Pedro, Matheus Cunha, Vitor Roque, Lucas Paquetá and Estêvão.

Moving onto Morocco, their most valuable player in insurance terms is the 27-year-old PSG right-back and captain Achraf Hakimi, worth £96m. Real Madrid’s Brahim Díaz, 26, is next, worth £58m, and he is followed by Leverkusen’s Eliesse Ben Seghir, aged 20.

And so to Scotland, where the model has Aaron Hickey, a 23-year-old full-back with Premier League Brentford, as the player with the biggest insurable value, of £44m. Andy Robertson, the Liverpool left-back who turns 32 in March, is second-most valuable, at just over £33m, despite being just three years from nominal retirement. Billy Gilmour, 24, is third, at about £31m.

While Robertson earns a big sum at Anfield — although perhaps just below the approximate £10m per year average among the first-team squad — he is entering the latter stages of his career.

lots of the Scotland squad are 30 or older, and hence their insurable value is lower

Scotland have their fair share of players making a living in the Premier League, which pays higher wages across the board than any other football division in the world, and at big teams in lesser leagues. But lots of these men are 30 or older, and hence their insurable value, by the model’s reckoning, is lower. They include Aston Villa’s John McGinn (31), Bournemouth’s Ryan Christie (30), Jack Hendry of Al-Ettifaq (30), Birmingham’s Lyndon Dykes (30), Hearts’ Lawrence Shankland (30), Norwich’s Kenny McLean (33), Hibs’ Grant Hanley (34) and Hearts’ Craig Gordon (42).

This is not to say that Scotland cannot cause an upset and maybe even get a result (draws being realistic best-case scenarios) against Brazil or Morocco. Their win over Denmark was a shock, after all. And of course they should beat Haiti, and that might be enough on its own to see them into the last 32.

But Brazil and Morocco, by any objective analysis, have better players, and you would expect them to finish in some order in the top two in Group C.

Personally, I think Morocco might top the section, with Brazil and Scotland also going through.

As for Haiti, they have a diverse squad mainly from small clubs (by international standards), often in minor leagues. Jean‐Ricner Bellegarde of Wolves is their most valuable player in insurance terms, but mainly because he’s on a Premier League salary, and the same can be said for Burnley’s Hannes Delcroix. Of the 26 players I think might get to the tournament with Haiti, 24 of them have an insurable value of less than £10m, and 11 of those have an insurable value of £1m or less.

The entire insurable value of the Haiti squad is not much more than half the sum of Vinícius Júnior on his own.

Shocks happen in football; that’s part of what makes it great. But Haiti are falling at the first hurdle, and Scotland, for the first time, are getting out of the group stage at a major tournament.

The Nutmeg Substack offers brilliant football writing, made in Scotland. Nutmeg also continues to exist as a hard copy quality Quarterly, published since autumn 2016. To find out about subscribing to that, there’s more information here.

My first piece for Nutmeg’s new Substack was about Scotland’s Millennium Bug and the second was about the dearth of Scottish talent in England’s elite division. The third delved into Tony Bloom’s interest in Hearts, an interest that has since become reality.

The fourth piece considered the financial administration of Dumbarton and the whereabouts of a missing £1.8m, and the fifth considered why the new-look Champions League is good for Celtic and bad for the rest of Scottish football (and clubs who aren’t big fish in their small ponds around Europe).

The sixth piece examined the putative Rangers takeover by the commercial arm of the San Francisco 49ers and their partners, and the seventh was about new owners putting the data into Dunfermline.

The next was about a long-awaited title for Royale Union Saint-Gilloise, revived by Tony Bloom, hero of Hearts. There was also a story of a Hibs player’s career allegedly damaged by a tackle from his manager. And a piece about the chances of survival in Scotland’s top flight after 15 seasons in the wilderness.

Next up was ‘Russell Martin: a deep dive into what his time at Saints means for his Rangers future’. Then ‘The miracle of Bodø/Glimt & what Scottish clubs can learn from a fellow small nation.’

And the last piece before today was “Hearts and Hibs broke transfer records this summer but success isn’t dictated by big buys.”