How the Old Firm (almost) played their part in détente

When a combined Celtic and Rangers team prepared to take on Dynamo Moscow in 1965, it seemed the Cold War itself might thaw. And then Hampden froze over

This article was originally published in Nutmeg Magazine Issue 21 (September 2021) and is free for you to enjoy. However, most of our content is paid, such as monthly data breakdowns from Nick Harris, Adam Clery’s tactical analysis, Daniel Gray’s Slow Match Reports and Stephen McGowan’s investigations. Sign up for your Nutmeg Season Ticket to get 12 months full digital access PLUS a year’s subscription to the beautiful, 200-page print quarterly delivered straight to your door.

By Michael Gallagher

It was the feeling everyone dreads: that moment when you look into your father’s eyes and think, “The old boy has finally lost it”. For me, this happened during Scottish football’s Covid-enforced shutdown.

With no football to look forward to, we only had the past to discuss. Gazing off into the middle distance, my dad tried to recall a hazy early memory of travelling to Hampden with his own father to watch, he claimed, a joint Celtic and Rangers side take on a team of Russians.

“This is a red flag,” I thought, and congratulated myself at such sparkling wordplay under trying circumstances.

Perhaps it made perfect sense. This is a man whose 1960s childhood was forged in the crucibles of two great conflicts: the global Cold War and the local, much hotter, Glasgow one. That his later-life delusions would fit into this framework should be predictable.

The idea of Glasgow’s green and blue factions teaming up to fight off the Red Menace seemed ridiculous to me, a worrying symptom of my father’s cognitive decline, and I made a mental note to follow this up. Of course, he was right. Almost.

The composition of an Old Firm XI is one of Scottish football’s most enduring, tedious questions. The beauty of the concept is that it is hypothetical: it can never happen, we will never find out, so we may as well argue about it. In 1965, however, this hypothetical question was, in a way, answered.

The story begins in November 1945. In the spirit of post-war cooperation, the Soviet Union sent their strongest side — Dynamo Moscow — on a high-profile tour of Britain, where they faced Chelsea, Cardiff and Arsenal, before travelling to Glasgow unbeaten to take on Rangers.

“Everyone in Scotland wanted to be there,” recalled the journalist Hugh Taylor, who reported queues for tickets two miles long with some prospective punters waiting 16 hours to secure their place. The lucky 90,000 packed into Ibrox were not disappointed.

Dynamo raced into a two-goal lead within 25 minutes, astonishing the crowd with their modern, technical football, but Rangers recovered to draw 2–2 and end the tour to everyone’s satisfaction.

Everyone except George Orwell, it seemed, who wrote his famous essay The Sporting Spirit in response. “The result of the Dynamos’ tour,” he asserted, “will have been to create fresh animosity on both sides.” Orwell went on to describe sport as “war minus the shooting”, a phrase that might also have been used to describe the escalating tension between the Soviet Union and the West in the following two decades.

This uneasy period culminated in the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, when the world stood on the brink of full-scale nuclear war.

What was required, clearly, was more football.

On the 20th anniversary of their groundbreaking tour, Dynamo again visited Britain and Rangers agreed to provide the opposition. Much had changed in the intervening years, in football as well as geopolitics. Gone was some of the Muscovites’ alien allure — to the great Bob Crampsey, the 1945 side resembled Martians — whilst friendly games were not the draw they once were.

As match day approached in December 1965 there was one further distraction: Scotland’s vital World Cup qualifier against Italy (described in detail by John Irving in Nutmeg issue 18). The Scotland squad included six Rangers players, meaning the Ibrox side would struggle to fulfil the Dynamo fixture. Risking a fresh diplomatic incident, manager Scot Symon asked for the match to be cancelled.

Celtic came to their rivals’ rescue. In the days before the game, Jock Stein agreed to allow his players to take part, thus creating an Old Firm XI. Stein’s motive was not entirely altruistic. As well as keeping his squad in “fighting trim”, he told the Celtic View, it would allow them to witness their counterparts from the Soviet Union in action; an important point since it was the first season in which sides from the USSR took part in European competition.

“We might draw Soviet team Dynamo Kiev in the next round of the European Cup-Winners’ Cup,” said the Celtic manager (they did, winning comfortably 4-1 on aggregate).

“It is to a club’s benefit that an official should be able to run the rule over strange opponents; it is even better if the players can see them up close in an actual match.”

The prospect of an Old Firm “cocktail team” — to be jointly managed by Symon and Celtic assistant Sean Fallon — tantalised the Scottish football community.

“The big question is whether two such shrewd football characters as Scot Symon and Sean Fallon can think up and put into operation a plan that will bring harmony to the six Celtic players and the five men of Ibrox,” wrote Gair Henderson in the Evening Times.

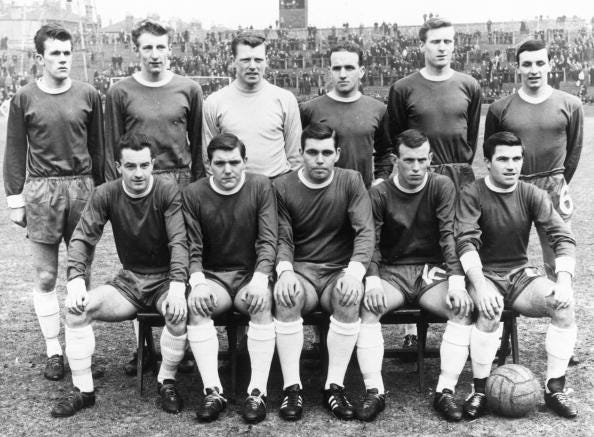

One would be forgiven for thinking such a side, shorn of its international stars and playing a non-competitive match in the dead of winter, would be composed of second-stringers and youths. It is a testament to the strength of the Scottish game that the squad contained 11 full internationalists (with more than a century of collective caps won over their careers), five European Cup winners, four Cup-Winners’ Cup finalists and a Ballon d’Or bronze medallist, not to mention the dozens of domestic honours they collected between them. A rag-tag bunch of reserves this was not.

The starting XI was announced in advance: in goal, Billy Ritchie; full backs Kai Johansen and Tommy Gemmell; a defence of Bobby Watson, John Cushley and John Clark; Jimmy Johnstone and Alec Willoughby on the wings; and an attacking trio of Joe McBride, George McLean and Bobby Lennox. On the bench were Ronnie Simpson, Roger Hynd and Davie Wilson.

Absent from both the Scotland squad and the select was Celtic’s Stevie Chalmers, who in the same week turned out in a reserve match against Hamilton Accies. If the recuperating Chalmers feared for his future, it would have been some consolation to know that 15 months later, in the Lisbon sunshine, he would score the most celebrated goal in Celtic history.

Match day arrived — December 3, 1965 — and the stage was set. Dynamo arrived in Glasgow having already faced Newcastle United, Stoke City and Arsenal on their tour, winning the first two games but losing 3–0 against the London side. The Old Firm select were ready to make history too, even reaching a compromise over their kit. In the first half they would wear the green of Celtic and in the second switch to the blue of Rangers.

Only one problem remained — the Scottish weather. The country was in the midst of a deep freeze more familiar to the visitors from Moscow, but on the morning of the game it was announced that it would still go ahead with kick-off delayed to account for the chaos caused by four more VIP guests in Glasgow that day: The Beatles.

The 8,000 fans with a ticket to ride to Hampden were more interested in Symon-Fallon than Lennon-McCartney. Would their experimental side come together and send Dynamo back to the USSR after a hard day’s night?

We will never know.

As kick-off approached, Dynamo took the field and lined up in formation, ready for action despite the freezing conditions. But there was no sign of their Glaswegian opponents.

“The crowd, not unnaturally, began to grow restless,” reported the Herald. Eventually, eight minutes after the scheduled start, the ball boys ran onto the field, removed the corner flags and ran back down the tunnel. A muffled announcement followed: the match was off.

“I was convinced that if the game had been started it would have been an ice frolic and not a football spectacle,” Fallon told the Celtic View. He and Symon deemed the pitch unplayable, despite Dynamo’s insistence that the game should go ahead.

Fallon was keen to provide a solution, however, and the match was rescheduled for Celtic Park the following day. Celtic were the only club in Scotland that protected its playing surface adequately, and the system (14 tons of hay on top) did its job. Unfortunately, the continued snowfall made the terracing and area around the stadium too dangerous to accommodate supporters. The match was called off again, this time for good.

Thus, the Scottish weather deprived the nation of a unique sporting moment. Might this strange spectacle have changed the course of Old Firm history? Would the sight of Jimmy Johnstone in royal blue or Davie Wilson in emerald green have led to a détente between the Glasgow giants and ushered in a new age of cooperation?

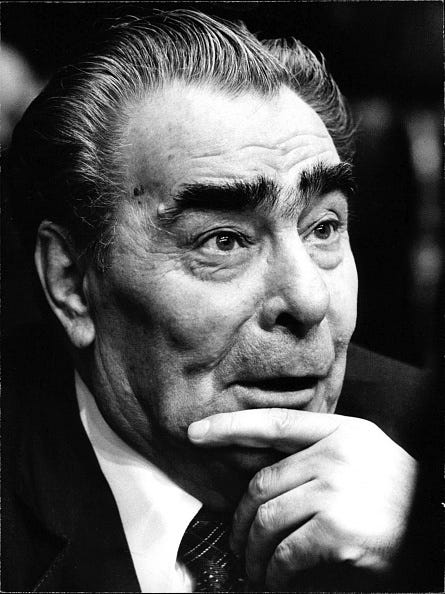

More than this: could it also have had global geopolitical ramifications? Would General Secretary Brezhnev, reading the sports pages back at Communist HQ in Moscow, have thought, “If even these two can settle their differences, perhaps we can sit round the table with our western enemies?” Might the Cold War have thawed right there and a new age of global peace followed?

My dad’s abiding memory of the occasion is trudging home from Hampden, despondent and frozen, his father cursing the complicated refund process and vowing never to go back.

One outcome of the debacle was a gradual realisation that football fans were being taken advantage of. An opinion piece in the Herald the following day — headlined “Football must shed cloth cap image” — criticised the game for having “not kept pace with other forms of the entertainment industry, of which it is a part.” It called for better, safer facilities for fans. This warning was not heeded. Just over five years later, on 2 January 1971, 66 supporters who attended the New Year derby at Ibrox did not return home.

A benefit match for the Ibrox Disaster Fund did eventually see Celtic and Rangers field a joint team of sorts against a Scotland XI, but under very different circumstances and bolstered by the likes of Bobby Charlton and George Best.

The abortive 1965 match was the first and last my dad and his dad attended together. Had it gone ahead, perhaps the pair would have created a lasting ritual around football, of pre-match pints and post-match rants, as he and I have done.

Last Father’s Day I tracked down the match programme as a present; all that remains of a curious incident in Scottish football history. Its pages offer a tantalising glimpse of what might have been, and, more importantly for me, prove that the old man is not yet losing his marbles.